How judicial conflicts of curiosity are denying poor Texans their proper to an efficient lawyer

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/2bcefb80f0682a32f44efa05f57de95e/02%20Indigent%20Project%20TM%20TT.jpg)

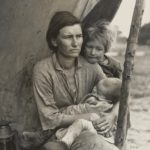

Marvin Wilford and his wife, Christine, have been married since 2006.

Trevor Paulhus for The Texas Tribune

This story is a collaboration between The Texas Tribune and Texas Monthly.

I.

It was going to be his last-place switching at the Velvet Lounge, and all Marvin Wilford felt was relief. It was November 11, 2017 — Veteran Day — and as he got dressed for direct, Wilford put on his scarlet-colored Marine Corps cap. The Velvet Lounge, a divest joint in North Austin, money itself on Facebook as “the official afterparty for the city, ” but Wilford couldn’t say he had fun: As a doorman, he collected cover charges from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. and did a lot of standing, sometimes outside. That evening, the temperature was in the 60 s. Over his T-shirt and jeans, Wilford attracted on a light-green hoodie.

It wasn’t that he felt heedless. Bald, with an athletic build, the 61 -year-old was a year away from collecting Social Security, and his veteran’s pension didn’t fairly cover the invoices. The sorority paid $100 a night–not the kind of money he’d became operating his own building-and-maintenance company once upon a time, but enough to supplement what his wife, Christine Wilford, brought in as a technician at Voltabox, a company that specialise in lithium-ion batteries.

In fact, Marvin Wilford felt lucky. After serving as a engagement Marine in Vietnam, he’d gotten in serious difficulties. In 1991, he’d been arrested after assaulting a police officer and was sentenced to prison for 20 years. He’d been secreted early, but then in 2006 he’d been arrested for assaulting an ex-girlfriend and was sentenced to another 10 times. A diagnosis in 2015 of post-traumatic stress disorder, and remedies, had given him a new start, but no one wanted to hire an aging felon. His nephew, who owned the Velvet Lounge, had shed him a lifeline.

Still, after 3 month at the gig, Wilford was done. He’d had hernia surgery, and he was walking with a cane. Christine Wilford had been sick, very, wracked by a nagging cough. The association, with its drunken clashes, was too unruly a scene. “This is not working for me, ” Marvin Wilford muttered to himself, hurling his cane in the car and heading west on U.S. 290. “There’s is about to be trouble.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/724609dcb3bb5b8f8f4be816b59410de/03%20Indigent%20Project%20TM%20TT.jpg)

Marvin Wilford sufficed as a duel Marine in Vietnam and was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder in 2015.

Trevor Paulhus for The Texas Tribune

Sure fairly, trouble came at around 4 a.m ., when a fight broke out by the dance floor and a security guard, a 42 -year-old called James Jones, escorted two women outside. Wilford, standing by the door, watched as Jones conducted the disheveled duo — one with no shoes — toward the parking lot. He and Jones had become friends, bonding over the annoying revelers they had to deal with. Jones liked to call him Unc, out of respect.

“F — all you security guards! ” yelled one of the status of women. She and her friend stumbled toward a car, vowing to return. Then they sped off.

Twenty minutes later, the same car screeched back into the parking lot. By this time, other patrons were spilling out onto the sidewalk. Though accounts of what happened next vary, various onlookers would later say they saw one of the women get out of the car, brandishing a tire cast-iron, and lunge at the collect horde. Jones realized the woman strike Wilford. Wilford reminisces trying to keep her away from other patrons. Someone smacked the woman over the heading with an empty vodka bottle. Someone else stomped on the scarf of the car.

“She was trying to fight everybody, ” Jones last-minute echoed. Quickly, the security guard grabbed his handgun and shoved it into her trendy. “Let run of the artillery or I will shoot you, ” he warned.

Instead, the woman rushed back into the melee. Jones and Wilford heard gunshots from somewhere in the parking lots. “Unc, going to be home the club, ” bawled Jones. Wilford ran inside as Jones parted his handgun into the air, shelling two counselling kills. The mob dispersed.

By the time the police arrived, just before 6 a.m ., the fighting had ceased. Various patrolmen interviewed those on the representation — Wilford, Jones, some added security guards and the woman who had charged the crowd, whose thought appeared to be bleeding. No one was arrested. When Wilford finally went in his vehicle to press home, it was light outside. “I’m through, ” he told Jones before leaving. “Too much madness over here.”

The security guard nodded. “I don’t blame you, ” he replied.

Five weeks later, Christine Wilford is passing through the mail when she opened an unsolicited kind character from a solicitor — she does not recall who — furnish his legal services. Her gulp caught when she saw why. There was a warrant for her husband’s arrest, read the note. The indict: exacerbated abuse with a deadly weapon, a second-degree felony.

The charge didn’t make sense. As a felon, Marvin Wilford wasn’t allowed to own a grease-gun, and didn’t. Neither he nor his wife had heard from the police. As Wilford skimmed the symbol, his head began to throb. With his criminal record, a brand-new decision could give him a life sentence. He felt his lungs restrict. He couldn’t breathe. Alarmed, Christine Wilford called the Veterans Crisis Line. Her husband was having an anxiety attack, she blurted into the phone.

Nine days later, on Dec. 29, the couple drove to the Austin Police Department headquarters downtown to turn himself in. Marvin Wilford had spent several days at a Veterans Affairs hospital because of his panic attack. Now, sitting with a detective in an inquisition area, he learned that the officers who interviewed him at the Velvet Lounge had not ascertained him credible. The girl in the fight claimed that she’d been threatened with a shoot by a serviceman wearing jeans and a light-green hoodie; she later picked Wilford out of a photo lineup. Harmonizing to a police statement, Jones told the officers that Wilford hindered a firearm in his gondola.( Jones disavows this, and when the officers checked the car that night, they found only Wilford’s cane .) There was video suggestion from a witness, the detective told Wilford, as he turned on a laptop.

Watching the chaotic cellphone footage, Wilford tried to protest. Yes, there he was, in his green hoodie. But, he pointed out, he was clearly deeming a cane , not a handgun. And Jones, he included, had recently learned of his warrant and willingly signed a notarized statement to support him, corroborating that Jones , not Wilford, had plucked the artillery and burnt it. Surely the police were interested in that?

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/866557311ac1e69b8e3db03e2d50ccc7/05%20Indigent%20Project%20TM%20TT.jpg)

The situation from a bond examine docket at the Travis County courthouse in July.

Trevor Paulhus for The Texas Tribune

The detective wasn’t persuaded. As Wilford was placed in handcuffs, his nerve hastened. He are not able to render a lawyer. His wife’s job just paid the legislations, and their impending asset excise pay that time — $4,500 for the home they’d acquired from his mother, in East Austin — loomed sizable. “I was really angry to be accused of something I didn’t do, ” he said later. “Especially with the record I have.”

In 1963, the U.S. United states supreme court regulated in Gideon v. Wainwright that a person accused of a trespas is guaranteed counsel even if the person can’t afford a solicitor. How precisely that counsel is provided, however, was left to states to decide, and in Texas, this “how” comes further demoted to the state’s 254 provinces — means that each district decides how to appoint, and compensate, advocates for the poorest of the poor. Last-place most recently completed fiscal year, there were roughly 474,000 indigent suits in Texas. There are 19 public defender’s offices, which 39 districts are dependent upon in some capability, but the majority of members of counties contract with private advocates, who are generally paid a modest flat fee per occasion.( This is the most common way that states fulfill their Gideon v. Wainwright obligations .) More than 150 counties also participate in a public supporter program for death penalty cases.

Travis County, where Wilford was booked, has a limited public advocate platform — it helps minors and some mentally ill accuseds — but relies mainly on a structure of controlled assigned guidance, in which an independent agency ascribes contingencies to a rotate given of more than 200 private advocates. After being transferred to the county jail in Del Valle, on the outskirts of Austin, Wilford waited.

He’d taken a few college castes on law after Vietnam, and he knew enough to feel hopeful. Surely his advocate would look into his fib. One evening in early January, he went to bed early — he was sleepy from the jail-issued anxiety meds — exclusively to be shaken awake by a patrol at 9 p. m. His lawyer, Ray Espersen, was there to see him.

A 58 -year-old with strawberry-blond hair and thin glasses, Espersen was one of Austin’s most prolific advocates: The previous year, he’d been paid for work on 331 misdemeanours and 275 misdemeanors in Travis County, as well as 46 felonies in neighboring Williamson County — more occurrences than nearly any other Austin-area attorney. Such was Espersen’s workload, in fact, that in 2015 it had caught the attention of the public, when local TV depot KXAN reported on the high number of cases appointed to him( the equivalent workload, by last-minute calculates, of that of at least three and a half solicitors ). After review reports, the district attorney’s office had opened an investigation into apparent discrepancies between the number of jail calls that Espersen had billed to the county and those recorded at the Travis County Sheriff’s Office.

Wilford did not know this. What he did know was that as he tried to explain — about the video, about the shoot, about Jones — Espersen didn’t seem to be listening. The visit office was insignificant, and the two sat essentially knee to knee, but “he was looking at the storey, scratching his head, appearing everywhere but at me, ” Wilford cancelled. According to Wilford, Espersen’s laptop remained closed, and he took no notes.

“Well, have your wife send me that video, ” Espersen said at last, according to Wilford.( Espersen declined to comment for this story .)

“Hey, ” said Wilford sharply, “I was just woken up to come talk to you, and I’m trying to tell you what happened because you asked. Now you’re not listening.”

According to Wilford, Espersen asked him to press the button that opened the room’s door. Unsure of what else to do, Wilford complied.

He would not discover his solicitor again for six months.

II.

Indigent defense in the U.S. is in crisis. More than 20 disputes filed in the past decade on behalf of poor plaintiffs — in California, Louisiana, Georgia and other states — point to this predicament, which has been acknowledged at the highest levels: In 2013, in a speech distinguish the 50 th anniversary of Gideon v. Wainwright, then-U.S. attorney general Eric Holder bemoaned the number of unjust beliefs and convicts endure by the poor. “This is unacceptable, ” he testified, “and unworthy of a legal organization that stands as an example to all the world.”

The main reason for this crisis is funding. Because the Supreme Court did not, in its 1963 decree, specify how states should pay for counsel, local policymakers facing other expenses — for institutions, arteries, law enforcement — systematically shortchange indigent defense. This is why public defender’s offices are chronically understaffed. It’s also why court-appointed private lawyers are overloaded: The rewards they’re paid are often so low-pitched that they are forced to take on a multitude of cases merely to make a living. Some overburdened lawyers, in turn, contribute to so-called plea mills, in which, critics say, they urge accuseds to assert guilty because they are either too marsh to investigate argues or incentivized not to.( In Travis County, for example, court-appointed solicitors are paid $600 for a transgression case whether they secure a plea treat or get the charge dismissed .)

The problem of funding is especially acute in Texas. Since 2001, when the state legislature transferred the Fair Defense Act — a statute that aimed to overhaul and standardize how the state’s poor received counseling — total spending on indigent defense has increased significantly, from some $91 million in 2001 to approximately $273 million in 2018. But Texas ranks among the states that spend the least per capita: Its counties, which shoulder most of the costs, are some of the fastest growing in the country, and what little the Legislature chips in to help — some $30 million last year — does not match demand. This starts a woeful game of numbers on the soil. In 2017, for example, the average court-appointed lawyer in Texas reached simply $247 per misdemeanor event and $598 per felony.

However, the problem goes beyond money. In Texas, the crisis is exacerbated by a key structural inaccuracy: Indigent defense is largely overseen by evaluates. Contrary to the American Bar Association’s principles of public defense, which call for defense lawyers to be independent of the judiciary, adjudicates in most Texas districts decide which solicitors get actions, how much they are paid and whether their flows — say, to reduce bail or measure DNA — have deserve.( Counties do have cost planneds for lawyers, but judges specified the following schedule and retain discretion over fee .)

Given that judges are elected based, in part, on the effectiveness of their laws, this is an inherent conflict of interest. “Whatever the judge wants to do, it’s probably not exonerate your client, ” said Charlie Gerstein, a advocate for Civil Rights Corps, a Washington, D.C ., nonprofit that has invested the past several years challenging criminal justice abuses around the country. “The judge wants to move the docket. The magistrate wants to get reelected.”( Civil Rights Corps filed the class-action lawsuit against the bail organization of Harris County in 2016.) Lawyers trying to work a subject properly — by devoting more go or seeking an inspector — face a quandary: Why see the effort if a reviewer can retaliate by appointing them to fewer actions or cutting their pay?

In 1999, Houston Democrat and then-state Sen. Rodney Ellis introduced a bill that they are able to, among other things, carry omission of indigent defense attorneys from referees to province officials. The Lege approved the measure, but evaluates, solicitors and prosecutors balk, writing more than 300 letters to then-Gov. George W. Bush.( “The bill inappropriately takes appointment authority away from guess, who are better able to assess the quality of legal representation, ” said Bush in his veto proclamation .) Two years later, Ellis helped muscle through the Fair Defense Act, which provided, for the first time, some fund and oversight by the state, in the form of an agency now known as the Texas Indigent Defense Commission. The TIDC was tasked with administering funds, enforcing standards and responding to breaches. But the law was also clear: “Only the justices … or the judges’ designee” was allowed “to appoint counsel for indigent accuseds in the county.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/25e031c0705947a4b4155977a858b808/04%20Indigent%20Project%20TM%20TT.jpg)

A replica of the state seal in the courtroom of District Judge Karen Sage.

Trevor Paulhus for The Texas Tribune

For a long time, the combined effect of this judicial switch and lack of funding — heavy caseloads, underserved defendants — was hard to quantify. But a astonishingly trailblazing move by the Legislature in 2013 returned Texas something almost no other state that relies on private attorneys has: comprehensive data. That time, lawmakers ordered every province to start reporting to the TIDC the number of indigent contingencies, and costs, be provided to advocates in every court. They also instructed the TIDC to conduct a study on relevant caseloads, the first of its manner mandated by a district government.

In 2015, the study’s results were liberated: In any opened year, researchers knew, a Texas lawyer could reasonably handle 128 felonies or 226 misdemeanors, or a weighted compounding of the two. This set a mark against which to understand the growing database, which indicated solicitors juggling two, three or even four times that load. Even the director of the TIDC at the time, Jim Bethke, said he hadn’t known “the magnitude of people who were getting run through the system on a super mass conveyor belt.”

Today, the TIDC database is staggering in its reach. With exactly a few sounds, anyone can look up solicitors by reputation and see how many indigent suits they took, and in what court and for how much. Finding the highest-earning attorney, or “the worlds largest” overloaded, takes hours. Consider exactly a few refers: In Harris County, in monetary 2017, James Barr gave more than $ 131,000 for work on 433 indigent misdemeanour contingencies, which all came from the court of Judge Jim Wallace. In the Panhandle, Artie Aguilar prevailed a contract in fiscal 2018 to handle all indigent felony specimen in Dawson, Gaines, Garza and Lynn counties — a total of 322 occasions, for support payments of $75,000. T. D. Hammons, who takes disputes around Amarillo, was paid $ 99,450 in monetary 2017 for work on 129 transgressions and dozens of misdemeanors. He reported that these took up less than 60% of his time, means that the rest of his time was devoted to additional clients.

Astonishingly, few guess — or solicitors or lawmakers — seem to be aware of these figures. Those who are will sometimes argue that caseload restrictions are impractical; it’s too arbitrary, “theyre saying”, to impose a number when places go from county to county, or when judges are faced with too many accuseds and too few defense lawyers. But as Texas germinates and funding continues to lag, these figures offer a sit to start–and one thing they show is that judicial omission of an indigent defendant’s right to a advocate is go untenable.

Just how indefensible is left to poor accuseds like Marvin Wilford to wrestle with — and for absurd challengers around the state to try to change on their own, as one young, recently minted advocate called Drew Willey discovered for himself. After graduating from the University of Houston Law Center in 2014, the green-eyed, sandy-haired 27 -year-old learned that he couldn’t take indigent suits in Harris County right away — the public defender’s office was too small and competitive, and courtroom appointments asked a few years’ experience. So he’d jeopardized into nearby counties, and soon he found work in the misdemeanor court of Judge Jack Ewing, in Galveston County. There, Willey was assigned to the case of an 18 -year-old called Wayne Lucas.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/010165b8130defc0f7320833e973dbd0/10%20Indigent%20Project%20TM%20TT.jpg)

Lawyer Drew Willey sits in the holding cell for accuseds on Galveston County’s confinement docket.

Trevor Paulhus for The Texas Tribune

Lucas had been tasked with burglary of cars. But when Willey went to see him in prisons, Lucas told a different story. He claimed that he’d been biking to a convenience store to buy cigarettes when a clamp from his bike fly off. He’d been looking around for the clamp, he said, when police officer presented up, saying that a witness had to be submitted to 911 that a male who adjust Lucas’ description was shaking the door of a car in a driveway. The men said the witness had filmed it with his cellphone.

Willey set into the case’s items. It was strange that Lucas was charged with burglary, rather than attempted burglary, since nothing had been reported stolen. The police forces mentioned the video, but after Willey solicited it from the district attorney’s office, he never got it. Willey queried Ewing to appoint an examiner, who interviewed the witness. The witness said that all he’d look was Lucas try to open the car door without success. The witness also disavowed taking a video.

It was clear there wasn’t much of a subject for burglary. Willey caused prosecutors to let Lucas plead to criminal mischief, a misdemeanor that he could eventually get expunged from his record. Lucas, who was training to become a manager at a Jersey Mike’s sandwich shop, was thrilled. He’d been in and out of jail enough times as children and juveniles. “I just wanted to get my life extending, ” he said.

Things would not be as straightforward for Willey as for his purchaser. When the lawyer referred a voucher for $1,320 for his task, Ewing approved only $ 511, quoting “excessive out-of-court hours.”( Although Galveston County compensates lawyers by the hour, the court “expects no more than 3.0 hours for commissioned lawyer to visit with defendant, fasten proposal from District Attorney’s Office, show offer to defendant and appear in court for the request or modification.”) Willey registered two petitions, after which he received the full amount.

But Willey soon determined himself in a blueprint. When he stuck a adjournment in another case and asked for $ 528, Ewing approved $330.( This time, Willey’s appeal was disclaimed .) When he asked for an investigator again, Ewing rejected any such requests. Meanwhile, Willey likewise began registering interminable gestures on behalf of clients who had been assigned to Galveston’s jail docket — a system in which accuseds who couldn’t open attachment were impelled, as he saw it, to allege in a hurried, assembly-line fashion. Then, in May 2016, Willey found out that four examples he’d been working on had been attributed to another lawyer.

Willey tried for several weeks to get a clear explanation from Ewing. Finally, in mid-July, he aimed the adjudicator out in his assemblies. Worried that Ewing would claim that he’d been an inept advocate, Willey decided to record the conversation so he’d have evidence of their exchange.( It is legal in Texas to record outside the courtroom and without the other party’s consent .) “Whoever I feel I need to appoint, I’m going to appoint, ” the judge told Willey. Willey couldn’t argue with that. But why, he invited, remove him in the middle of these cases? Didn’t changing lawyers midstream hurt a defendant’s ability to get the best representation?

Ewing originated impatient. In the year and a half he’d been a judge, he illustrated, Willey was “the only attorney that has, on almost every case you’ve had in my court, asked for an appointment of an investigator.”( Willey told me that he asked twice .) Ordinarily, he supplemented, advocates in his courtroom money three hours for alleging out a case, for about $198.

“I applaud your wanting to help and get the best deal you can for these beings, ” the reviewer continued, but Willey’s greenbacks were unwarranted. “I can only count and pay for what would be reasonable.”( When contacted for mention, Ewing did not dispute the words from Willey’s recording. But, he emphasized, context was important. He wasn’t the only one to affirm Willey’s full sought remittances; so had two other adjudicators in Galveston County, and Willey had not struggled those. As for the reassignment of Willey’s jail docket lawsuits, Ewing pointed out that the lawyer he threw them to had, unlike Willey, 28 years of event. Furthermore, according to Ewing, it is not uncommon for jail docket defendants with other pending events to be reassigned to lawyers who ever representing them .)

Willey was stupefied. He was caught in a organisation, he realized, that didn’t allow him to really represent his purchasers. The adjudicate, forced to apportion scant assets, was caught, very. “How could things have grown this bad? ” Willey wondered as he left the judge’s assemblies. “How could nobody stand up? ”

III.

Back in Travis County, Wilford tried to clear his head. Had he upset his solicitor? Did he still have a lawyer? Espersen had given him a business card. Before heading back to his cell, Wilford arranged a call to his wife. The meds were moving him fuzzy, he informed her; he was worried he’d messed up, and he needed her to call Espersen.

Christine Wilford was used to calls from confinement. She and Marvin Wilford had married in 2006, right as he began his second stint in prison, and much of their relationship had been defined by rails. A native of France, she wore tiny, chunky-frame glass and hindered her fuzz in golden-brown yarns; a tattoo on her wrist featured her husband’s nickname, Blocko, in cursive words. She told him not to worry.

The next morning, she contacted Espersen, who briskly confirmed that he was her husband’s lawyer. But over the following address few weeks, according to Christine Wilford, Espersen did not pick up or return her bawls. Marvin Wilford called Espersen, extremely, with no success. The ex-serviceman tried to distract himself, doing push-ups in his cadre and read the Bible( “the book of Psalms, the whole way through, ” he said ). Christine called on Wednesdays and Saturdays, and the two became friendly with his cellmate, a former Army Ranger.

At least twice, Wilford was given a court date merely to learn that the hearing was retarded. By late March, he had sat in jail for virtually 12 weeks with no message, according to him, from his lawyer.

What neither he nor his wife knew is that this was exactly how things were not supposed to go in Travis County. More than three years earlier, on its own initiative of a adjudicator listed Mike Lynch, the district had rewritten the system by which it provided for poor accuseds. Lynch, who was well known around the courthouse — he’d acted as a defense lawyer, a prosecutor and for two decades as a magistrate — had grown troubled by the role of adjudicators in overseeing indigent security. For one thing , no one had the time to assess defense lawyers’ concerts. The magistrates assembled over lunch twice a year to review which attorneys were qualified to take appointments, but the process felt arbitrary and era consuming.

There were also disagreements over pay and allegations of favoritism. Although judges were supposed to appoint attorneys from a rotating “wheel” of identifies, they often did not; in 2014, for example, courthouse records was indicated that judges made almost half of their appointments from the bench.( “Several of them were always delegate the same handful of advocates, ” said criminal defense lawyer Betty Blackwell .) This means that some solicitors got an overabundance of cases, while others felt forgotten. Amber Vazquez, a advocate known among accuseds as the Queen of Acquittals, said she was removed from the wheel in 2012 after numerou quarrels with various justices. “I was challenging everything, as a defense attorney is supposed to do, ” said Vazquez. “Then the pushback started.”

With a committee to help him, Lynch probed for an alternative. A full public defender’s office was too expensive — some $33 million a year — and would likely meet with resistance for chipping into private attorneys’ income. So instead, Lynch turned to managed apportioned counseling, a framework pioneered in San Mateo County, California, that had also been adopted in Lubbock County. In that arrangement, both governments still contracted with private lawyers, but an independent position — rather than the adjudicates — oversaw appointments and payments. Lawyers had strict caseload limits and easy access to investigators, they were paid not just for taking occurrences but likewise for filing motions and working outside the courtroom, and they received frequent performance evaluations.

Intrigued, Lynch drafted a proposal to create a similar example in Travis County, and in early 2015, an independent place known as the Capital Area Private Defender Service opened its openings in Austin. In law cliques in all regions of the country, the move — highly significant for an urban county in Texas — was heralded with prudent hope. Austin Lawyer called it “the culmination of decades of uneven attempts” to establish fair representation for the poor, while a government study out of Michigan was ultimately has pointed out that “CAPDS provisions a high quality model for reform.”

The office, located for a era on the seventh floor of the Travis County courthouse, was minuscule, with no openings, and its first two works — executive director Ira Davis and his agent, Bradley Hargis — had experience as court-appointed lawyers, though none in a public defender’s office. Still, things felt hopeful. The next hire, Trudy Strassburger, had recently moved to Austin after labouring as a finagling lawyer at the Bronx Defenders in New York. She brought the intensity of an foreigner, as well as expertise in “holistic” defense: the idea that effective representation of low-income parties requires not just law but too social support. She persuasion the department to hire an immigration lawyer and two social workers.

Almost immediately, terrace appointments slumped. And now that advocates did not have to persuade a judge to pay for an investigator — they expected CAPDS instead — investigations increased, from fewer than 100 per year to more than 400 per year.( The number of case expulsions also increased .) Any lawyer who wanted to receive appointments had to apply with a review committee; an analyst crunched amounts on case outcomes. Frustrated categories could call CAPDS if they were having problems. “All day long, the telephone hoops, ” Davis told me.

Christine Wilford learned about CAPDS from a social worker. Desperate for help, she expected the social worker to call the office. Was Espersen still even her husband’s lawyer? Yes, came the answer. But, according to the Wilfords, they still did not hear from him. A courtroom date of March 29 came and get with another continuance.

Finally, in the early morning of April 12, Christine Wilford received a request from her husband’s cellmate, who said that Marvin Wilford was on his route to field. She drove downtown, arriving at the courthouse well before 9 a. m. She made her mode past defence, up eight floorings, to the courtroom of Judge Karen Sage, where she’d been told she’d view Wilford. Before taking a seat, she found the bailiff.

“Do you know if Mr. Espersen is here? ” she asked. She had no idea what he looked like. After a prosecutor parted him out, in an area reserved for lawyers and tribunal staff, Christine Wilford waited for him to approach her.

Espersen rejected frequently to be interviewed for this story, though I called and emailed many times over several months and followed him around the courthouse for a week.( When I asked for a chance to explain my reporting and include his perspective, he replied, “I like surprises.”) By all notes, however, he is well liked by Austin’s magistrates, who appreciate his knowledge of Spanish and his willingness to take over unpalatable disputes, such as aggravated sexual assault.

“He’s got tough skin, and he’s competent, ” said Judge Brenda Kennedy, who has appointed him in the past to deal with uncooperative patients. “He’s still able to represent and sometimes get results for them.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/544705f8279824b5323733acd34eb5df/07%20Indigent%20Project%20TM%20TT.jpg)

Case enters at the Harris County public defender’s department in Houston.

Trevor Paulhus for The Texas Tribune

He is known as much for plowing through his daily caseload — 11 court proceedings on average, he told the Austin American-Statesman in 2014 — as for his sense of humor. “So this, now, is like a sexual routine, ” he formerly declared in a courtroom about jury excerpt, according to a blog post by prosecutor Mark Pryor. “We’re feeling each other out, getting to know mysteries about one another.”

So it was likely not out of character for Espersen to walk over to Christine Wilford and, after she innovated herself, smile at the slew of her long braidings. “Oh! ” she recalls him saying. “Are you related to Milli Vanilli? ” Before she had a chance to answer, he did a bit dance.

“Girl, you know it’s true, ” he sang, resonating the chorus by the famously lip-synching ’8 0s dad duo.

Christine Wilford, who had never heard of Milli Vanilli, was so taken aback that she no longer remembers the rest of their exchange, except for the fact that her husband’s court date was again pushed back. Espersen is not communicate with Marvin Wilford, who was sitting in a holding cell at the courthouse before being taken back to jail.

When Wilford returned to court a month last-minute, his wife detected Espersen again. She wanted to get the lawyer textiles that could be helpful to the case, she told him: a register of observers who are likely demonstrate Wilford’s account, his medical and military records, the statement from Jones. That night, after the bag got another continuance, she texted the directory of evidences to Espersen’s phone, then headed to the Dollar Tree to buy an envelope. Carefully, she wrote the address of Espersen’s office on it, stuffed copies of Wilford’s documents inside and mailed it.

On June 22, Wilford had another court date. Harmonizing to him and his wife, the couple had still not heard from Espersen, and to their knowledge , “no ones” contacted the witnesses or Jones.( In fact, Espersen soon informed Christine Wilford that he never received the documents ). But the working day, Espersen sought that the case be put on the trial docket — a potentially favorable move, in that it might force the prosecutor to look harder at the example and perhaps even dismiss it.

In the courtroom, stance with Espersen before Sage, Marvin Wilford felt confused — and exhausted. He gazed his lawyer. It was the first time they were meeting each other since that fazing darknes in prisons, yet Espersen just spoke to him. The judge asked for his response to the charges.

“Not guilty, Your Honor, ” said Wilford.

IV.

As he left Galveston, turning his white SUV onto Interstate 45, Drew Willey fumed. In the weeks after Ewing first removed him from his suits, he’d been so upset that he’d filed a complaint with the Texas State Commission on Judicial Conduct, leaning the canons of the Texas Code of Judicial Conduct that he made Ewing was flouting: “Most importantly, Canon 3, C.( 4) by failing to exercise the influence of appointment impartially and on the basis of merit.” Now, as he saw it, the adjudicator had spelled out in his own words what Willey had suspected all along: There were inadequate accuseds who were not getting a fair shake. Willey announced his wife in Houston. “You’re not going to believe what this chap just said, ” he told her, his voice shaking with anger.

He knew what some of his advocate peers said here today — that he was too idealistic. The territory committee was notoriously opaque. And the Texas Indigent Defense Commission, which Willey too registered objections with — over Galveston’s jail docket — couldn’t do much either. Technically, the TIDC could make recommendations, but judges were not compelled to follow those; the agency could also keep mood fund, but it had said and done only once, in 2015, after it found that two attorneys in Hidalgo County received more than a third of all 1,900 adolescent indigent suits in one court.( Two year later, one of the lawyers was still receiving the second-most juvenile cases of any lawyer in the province .)

“It takes a lot of sacrifice, having that defend, ” said Brandon Ball, a lawyer in the Harris County populace defender’s office who has worked with Willey. “They overpowered you down. They thumped you down. They beat you down.”

But the fight is what had attracted Willey in the first place. He’d grown up as a middle-class republican in Arlington, the youngest of four, with a love of math. Gifted and competitive, he was president of the student body at his high school. After majoring in business at the University of Texas at Austin and prosecuting a master’s in taxation statement, he’d enrolled in law school to become a tax attorney.

A summer internship at the University of Houston’s death penalty clinic modified that scheme. Willey was assigned to the case of Marvin Wilson, a 54 -year-old mentally disabled black man from Beaumont who had been sentenced to death in 1994 for the deaths of a police informant. Wilson claimed he was innocent, but the clinic’s advocates hoped to spare him fatality by are concentrated on his mental fitness. Willey was tasked with retyping the transcripts from Wilson’s trial, and as “hes working” through them, he changed is concerned about what he felt were grave indiscretions by Wilson’s attorney. The territory claimed, for example, that both the victim and the murderer were black. But a filament of Caucasian hair was found in the victim’s hand, a known fact that had not been able to been explored.

Willey had leaned generally in favor of the death penalty, but the consequences of shoddy defense work stimulated him do an about-face. He made it upon himself to investigate Wilson’s case, even interviewing bystanders in Beaumont — an compulsion that exasperated his foremen, who needed his focus on other matters. When Willey toured Wilson on fatality row, he was struck by Wilson’s positive prognosi. “You’re not giving up, ” Willey recollects thinking.

But by Aug. 7, 2012 — the day Wilson was to be executed — all of the requests on his behalf had been denied. That evening, Willey drove to a Bible study he regularly attended. He’d become more connected to his Christian faith in college, and now he felt disheartened. At sundown, as the study leader cracked open a Bible, all Willey could think about was how Wilson was strapped to a gurney, sucking his last wheezes. He was staring at the floor, “ve lost” saw, when the ruler speak the night’s passage, Proverbs 31:8 -9. “Speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves, ” it croaked. “Defend the rights of the poor and needy.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/c333381a03ef7f546a419a7973c0fcfd/06%20Indigent%20Project%20TM%20TT.jpg)

Kimberly Clark-Washington, a mental health clinician, works at the Harris County populace defender’s place in Houston.

Trevor Paulhus for The Texas Tribune

The texts made Willey like a lightning bolt. His calling wasn’t tax law, he recognized. It was to defend the poor. “My jaw was on the flooring, ” he said. “That message was my brand-new guidebook in life.”

Willey signed up for a mentoring platform through the public defender’s office and, after graduating from law school, acted a few months for a criminal defense attorney in Houston before getting on the appointments list in Galveston and Fort Bend counties. His eventual hope was to work in Harris County, which he figured could use the help: Its solicitors were notoriously overburdened, and its judges had come under fuel in the media for cronyism. In one far-famed illustration, the Houston Chronicle had reported in 2009 that advocate Jerome Godinich missed deadlines in death penalty cases and carried a high caseload. Six year later, Godinich still managed nearly 500 trespass a year, including various capital carnage actions. Most of his appointments came from Judge Jim Wallace; Godinich was one of Wallace’s top expedition donors.( Godinich and Wallace did not respond to requests for comment .)

But Willey needed ordeal, so he focused on his work outside Houston. On his weekly drives, as he attracted away from his townhouse in the Montrose neighborhood, he thought often of Wilson, whose photo he kept in his home office. There had to be another way of doing this work, he mused.

In the sink of 2015 — as he was looking into the Wayne Lucas case — the answer came to him. A few defendants in Harris County had heard that he represented good their customers and called him from county jail; they wanted to know if he could take their cases because they weren’t hearing from their court-appointed solicitors. Willey turned them down. Without was nominated, he had to work pro bono, and he couldn’t afford to do so. Then, driving one afternoon, he had an idea: What if he had been able to develop funds for the cost of defending occasions?

On January 17, 2016 — just before Martin Luther King Day, a deliberate selection — Willey picked friends and family at a eatery and announced his propose: He was starting a nonprofit announced Restoring Justice. To figure out an appropriate workload and how much money to raise, he would use the TIDC’s study on caseload restrictions.( For a first-degree-felony case, for example, he figured he’d raise $5,000; this was far less than an advocate would blame a paying purchaser but much more than most court-appointed advocates receive .)

That spring, as his conflict with Ewing began to heat up, Willey threw himself into the nonprofit, crowding out paperwork and enlisting members of the security council. He also took on one of its first buyers, a soft-spoken 27 -year-old named Maurice Johnson, who was in jail for sexual assault of a minor. Johnson claimed that the victim, his lover, had lied about her age, but he’d pleaded guilty after being told by the investigator that she and her papa would testify against him.

Johnson’s court-appointed lawyer, Ruth Yvonne Burton, had not inspected him in prisons; they’d spoken only on periods when he appeared in court. When Willey got the investigator’s memorandum, he has understood that the investigator “ve never” interviewed the main victims or her father, that the victim had admitted to the police that she’d lied to Johnson about her senility, and that the papa had agreed to accept a lesser charge against Johnson — a fact that Johnson had not been told. At the sentencing hearing, the public prosecutor asked for a sentence of 15 years. Willey persuasion the reviewer to give Johnson three.

Burton was paid for work on 361 transgressions in fiscal 2016. When I contacted her in a brief phone conversation, she defended her caseload, pointing out that various researchers toiled in her department. “I don’t help anyone to plead, ” she said. “I will tell them what the facts of the case are.” When it came to Johnson, she said , not knowing the girl’s age was not a defense. “That doesn’t form you not guilty, ” she said.

As Willey interpreted it, though, having all the facts still made a significant contribution. “It things in how you negotiate for someone, in how you adjust punishment, ” he said. “It problems a lot.”

Willey had known that Burton had a high caseload, but it wasn’t until months later that he realise just how high. He was at his desk one day, poring over the TIDC website, when he discovered that the agency not only issued caseload guidelines — as he knew — but also obtained detailed data for all advocates doing indigent defense.

Clicking around the database, Willey was outraged. He’d figured exclusively a handful of lawyers didn’t have epoch for their clients, but there were scores of them — and not just in Harris County. Court-appointed lawyers all over Texas had workloads two or three times the recommended limit. “It was kind of a hallelujah instant, ” cancelled Willey. “I unexpectedly had this objective checkpoint on adequacy of counsel.” Now, it dawned on him, he didn’t have to rely on referrals or announcements from prison. Thanks to the database, he could figure out who most needed facilitate — and go after those patients himself.

He was still mulling this over when, in October 2017, the State Commission on Judicial Conduct voted to dismiss his objection about Ewing. “In its discretion, the Commission determined that the judge’s conduct in this particular instance, while not inevitably relevant, did not rise to the level of sanctionable transgression, ” settled relevant agencies. “The Commission remains confident that the manage will not occur in the future.”

Willey shook off his frustration. He would just move on, he decided, and double down on his nonprofit. So when, that same month, he received a phone call from Charlie Gerstein of Civil Rights Corps, Ewing was far away from Willey’s mind.

Gerstein was calling for advice on a consumer, and as the two chitchatted, the conversation turned to indigent defense. Most suits on behalf of the poor, said Gerstein, get after high caseloads and inadequate resources, but lately he’d been thinking about guess. If a solicitor faced resistance from a evaluate, then it didn’t matter if he had all the resources in the world. What if, Gerstein invited, there are still a room to address judges’ retaliation against advocates who tried to adequately represent their low-income patients?

“Wait a second, ” Willey replied. “That happened to me! ”

His and Gerstein’s intellects began to race. Willey had been trying to bypass the system through his nonprofit, but perhaps, it followed to him, there was something bigger he could try.

Five months later, with Gerstein as his solicitor, Willey filed a suit against Ewing.

V.

On June 24, 2018, Marvin Wilford sat on his bunk in the Travis County jail and drew out a diary. Every other week, Christine Wilford mail him coin for the commissary, and he’d been intentional with his purchases: $2.50 for the diary, 50 cents for a pen, 42 pennies for a stamp and envelope. He began to write a letter to Sage, the evaluate in his lawsuit. He was fuelling his solicitor, and over three pages, he did his best to explain why: Espersen just communicated with him; it showed he’d misplaced documents issued for Christine Wilford. “He didn’t use none of the state money … to get an investigator to question the witness on my behalf , not even the Security Guard who shelled the gun, ” he wrote.

The thought that he might end up in prison for many years overtook him. “When I was in combat, and my life was on the line, I fought for my life, ” Wilford recalled. “And I recognized,’ I gotta fight for my life now, too.’ I was trying to write the character so she would understand.”

For two weeks, neither he nor Christine Wilford got a response. She called the Capital Area Private Defender Service phone number repeatedly — more than 20 epoches, she belief — and left message after word. Ultimately, in early July, she discovered from chairman Ira Davis, who told her to attend her husband’s next tribunal time, on July 13. More waiting, she envisaged. If CAPDS was supposed to be a recourse, it didn’t strike her as particularly effective.

The truth was, the staff at CAPDS was overwhelmed, very. The sheer volume of manipulate — supervising more than 200 lawyers, handling their payments, coordinating investigators and social workers — was near impossible for such a small team. Not to mention the number of complaints they received. There was just time to look into each defendant’s grievance, let alone a lawyer’s performance. Many complaint formations ended up half filled out, with no record of a follow-up.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/25ea98dffc4e2fc718352d2311464eb7/08%20Indigent%20Project%20TM%20TT.jpg)

Boxes of case files at the Harris County public defender’s department in Houston.

Trevor Paulhus for The Texas Tribune

Strassburger, the New York hire, was particularly forestalled. For all the promise of the managed earmarked solicitor representation, she felt that CAPDS’ presumably independent omission was persistently jeopardized. The implementation of sleuths, while better, was not improving fast enough; by 2018, advocates were requesting them in less than 5% of offense the circumstances and less than 1% of misdemeanor contingencies. And while justices no longer ascribed lawsuits — this was left to court administrative staff — a solicitor could still show up for ad hoc appointments, circumventing the setup.

When CAPDS planned a client’s bill of rights, certifying, among other things, a defendant’s right to see his advocate, the Austin Bar Association refused to sign off on it. “Some advocates were afraid that clients would use it to try and file grievances against them, ” explained lawyer Betty Blackwell, who sits on the board for CAPDS.

Because guess had found it difficult to suspend inadequately acting advocates, CAPDS had formed a review committee of criminal defense lawyers to manufacture the tough labels instead. But, as it turned out, lawyers knew it just as difficult to sanction their peers. Committee members were willing to kick collaborators off the pedal, thereby depriving them of income; they also had trouble make defendant grumbles at face value. “People in the criminal justice system are disappointed, ” clarified Blackwell. “People are going to complain about their lawyers.”

Most exasperating to Strassburger, however, was that despite the county’s effort to wrest power from the adjudicators, the judges were, in her sentiment, still ultimately in control. The refresh committee actively begged judges for input on lawyers.( Amber Vazquez, for example, who was booted off the wheel before CAPDS was created, still could not get high-level felony appointments in the new system; her lotion was rejected due to unspecified “judicial complaints.”) The field faculty that facilitated appointments likewise declared to the justices. Meanwhile, the evaluates refused to agree to stricter caseload restraints.( The limit in Travis County is 100 misdemeanor cases and 90 crimes at any given time; Alex Bunin, the honcho supporter in Harris County, “ve been told” that lawyers in its term of office rarely go above 30 transgressions at once .) Judges likewise, together with county commissioners, refused to increase lawyers’ rewards, arguing that there wasn’t fairly funding.

As a ensue, many lawyers still juggled big caseloads, racking up accusations. At first, Strassburger tried to keep detailed memoes. In July 2015, for example, she noted that several defendants had complained about Tom Weber, who that year was paid for 305 crimes and 104 misdemeanors. “All reported fantastic and unprofessional behavior, ” she wrote. When she’d accompanied this to Weber’s attention, Strassburger also wrote, “hes had” rejected the credibility of his clients, calling them “monsters” and “scumbags” and “rapists.”( Weber did not respond to requests for commentary .)

Three weeks after that memoranda, the KXAN report about Espersen’s workload aired. According to the investigation, over two years, Espersen had billed Travis County for 40 hours of confinement visits that were unaccounted for. In one speciman, Espersen claimed to have met with an inmate referred Rodney Thomas five times, for a total of 13 hours. But Thomas told KXAN that the lawyer inspected him formerly — a week before his trouble — a claim corroborated by jail records. Espersen had also money for a visit with Robert Rivera, who told KXAN, “I did not so much as receive one call from Mr. Espersen while incarcerated at Travis County Correctional Complex in Del Valle.”

In response to the KXAN report, the district attorney’s office opened a criminal investigation into Espersen and a few other lawyers — including Weber — for the suspect overbilling. When the CAPDS review committee gathered early the following year to decide which lawyers could take appointments, Strassburger, Davis and Hargis recommended in a joint memoranda that Weber not represent people with mental illness. He’d reportedly told one client to “go ahead and kill himself, ” they wrote. They urged the committee to “seriously consider whether he should be defending indigent parties at all.”

They too counselled about advocate Phil Campbell, who was paid on 134 trespass and 300 misdemeanors in monetary 2015. “Staff watchings of Mr. Campbell and complaints from other lawyers demonstrated an attorney who was not truly preaching on behalf of his patients but merely imparting an proposal and cautioning them to take it, ” they wrote.( Campbell declined to comment for this story .) Later, they brought up Espersen. Some of his purchasers had learned of the DA’s investigation and written to CAPDS to complain. “I deserve a gala trial, ” wrote one. “Please help.”

The review committee agreed to remove Campbell and Weber from matters involving people with mental illness. But that was it. Weber continued to receive appointments on high-level misdemeanours until he was hired by the DA’s office. Campbell’s caseload, meanwhile, increased; he went on to take suits in nearby districts.( In 2014, he was paid for 106 misdemeanours and 252 misdemeanors; by 2018, his misdemeanor caseload had grown to 428.) As for Espersen, the committee decided to delay action until the DA’s office concluded its investigation, which is still pending four years later.( The DA’s office revoked a public information request for records related to the investigation .)

As long as evaluates had this much say in the matter, Strassburger realized, little would improve for Travis County’s good accuseds. Her despair merely grew when, in the fall of 2017, several referees approached CAPDS with a few questions. Was it fair, they requested, looking to see a lawyer’s number of cases rather than purchasers? Given that some consumers had more than one case against them at a time, why not instead suspend advocates who had too many buyers?

Strassburger was dumbfounded. This would have the effect of raising the caseload limit, and caseloads were terrible fairly. In yet another memo, she sketched her concerns. “We are encouraging lawyers to quickly resolve cases and, in effect, penalise those attorneys who hold complicated examples, ” she illustrated. In fearless, marked font, she added, “The attorney with the highest caseload( 748) has not been suspended for outstrip caseload restraints in the last 12 months.” A few months later, discouraged, Strassburger quit.

On July 13, Marvin and Christine Wilford loomed for his field appointment. They were joined by Espersen, who, per Marvin Wilford’s petition, had agreed to remove himself from the case. Standing before Judge Clifford Brown — who was sitting in while Sage was at trial — Wilford listened attentively as the referee approved Espersen’s motion. Wilford rustled with relief. “Finally, ” he thought.

VI.

“I’m a taller lily-white buster with pitch-black cowboy boots, ” said Willey. It was November 2018, and he was describing himself on the phone to Hattie Shannon, one of “the worlds largest” overloaded court-appointed solicitors in Harris County; the previous year, she’d been paid for work on more than 430 trespass. Willey was hoping to meet her at the courthouse.

In the eight months since filing his litigation, Willey had been hectic: He and his wife had welcomed their first baby, a boy, and he was raising monies in earnest for Restoring Justice. He’d moved his office to a tiny room on the first floor of a house in the Heights neighborhood and was taking on more clients — by the end of the year, he’d have 19 active disputes. It wasn’t a huge number, but as he liked to point out, the nonprofit had saved accuseds a combined 49 years of incarceration.

He now quarried the TIDC database regularly, cross-referencing the data with active occasions is available on the website of the Harris County District Clerk. This is how he’d concluded his newest target: a 30 -year-old woman arrested for PCP possession who had been sitting in jail for six months. Her lawyer was Shannon.

The woman’s bond had been established at $10,000, which hit Willey as inordinate, since it was a nonviolent charge. Shannon had registered a few gestures, but nothing were to lower the bond, so Willey toured the woman in jail and recommended taking her occurrence. When Shannon did not object, the woman was thrilled.( Shannon did not respond to requests for comment .)

On the phone, Willey arranged to meet Shannon the next day in the courtroom of Judge George Powell to finalize the handover. Immediately afterward, he called the woman’s mother, who confirmed that the family could afford to pay a reduced bond. She had announced Shannon several times, the mother said, but has already reached her exclusively on the night before her daughter’s court date.( Jail records register Shannon inspected the status of women once .) Her daughter, she continued, had made some bad choices, but she’d grown up in church and wanted to be a paralegal. Now Thanksgiving was around the corner. “I want her home for the holidays, ” replied Willey.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/ab847c8b53c6e0932e776d7fcf487879/01%20Indigent%20Project%20TM%20TT.jpg)

The Capitol can be seen from the Blackwell-Thurman Criminal Justice Center in downtown Austin.

Trevor Paulhus for The Texas Tribune

He hung up and smiled. His lawsuit against Ewing had done national headlines, be recorded in The New York Times, and he’d been receiving letters and donations to his nonprofit from all over the country. Lawyer around Texas had written to share their own run-ins with referees. A schoolteacher in Florida had mailed him some framed paraphrases from the Gideon v. Wainwright case. They sat in his office now, near the photo of Marvin Wilson. “Every case I take over, I ensure the person has potential, ” said Willey.

On its face, the lawsuit was a long shot. Guess, like attorneys, enjoy broad exemption for their actions, on the principle that they should be free to fix senses without unnecessary horror of redres. In Texas, after two lawyers registered dress against referees — one in Travis County in 2006, another in Tarrant County in 2007 — for eliminating them from cases and appointment directories, both cases were rejected. In Ohio, when a public follower sued a judge in 2012 for removing him from dozens of offense subjects, the 6th U.S. Route Court of Appeal sided with the judge.

But the lawyers in those cases indicted on the basis of lost income. Willey’s case was intentionally different. He was suing not for shatters but for the right to advocate for his clients. Willey’s lawsuit argued that government contractors — which court-appointed lawyers are — have the right not to be fired from their jobs for speaking up. In addition, Willey was asking for declaratory relief, a statement from the courts acknowledging that if Ewing retaliated against Willey again, he would be in violation of the law. The rarity of the coming presented the occasion a chance of success — and offered a possible precedent for how to coerce change in Texas.

The next morning, a chilly 35 degrees, Willey got in his SUV and headed to the courthouse. In a small, trapezoid-shaped room that was serving as a makeshift courtroom for Powell after Hurricane Harvey, Willey waited for Shannon. When she didn’t show, he approached the magistrate on his own to utter his action for lowering the woman’s bond: Her parents wanted her back, and she’d acted six months. The lawyer, a young-looking man in a checkered blazer, objected, reading out the woman’s previous criminal charges — controlled substance possession, a couple of DWIs, wealth of marijuana.

Willey pressed again, irritating the gues, who fostered his expres. “At this extent, you’re not even attached to the case, ” said Powell. “Let’s handle that first and then get back together on it, all right? ”

Outside, Willey wheeled his eyes. “That’s the culture, ” he fumed. “He basically said to get the hell out of his face.” He debated going back, then speculated better of it. He didn’t want to oblige the justice angrier. He’d wait.

His bet paid off. A week last-minute, Powell agreed to a personal bond. Willey was elated — his buyer would be home for Thanksgiving.

When I called Powell to ask about the occurrence, he showed he’d grown testy in the courtroom because it wasn’t clear to him that Willey had entered the paperwork to take over. “The fact that he was discussing the lawsuit with me was an ethical question, ” he justified, “so I just shut things down.”

Powell said he hadn’t given much thought to why the woman had sat in jail on a $10,000 bail for several months with one solicitor and come out on a personal bond after a few days with another. “Ms. Shannon is a good attorney, and she works very hard, ” said Powell. But he hadn’t known her caseload — or that 99 of the 430 misdemeanours she’d been paid for the previous year were in his law. “I wasn’t aware, ” he “ve been told” after I rehearsed the numbers. “That’s interesting. Tell me the numbers again, satisfy? ”

VII.

“Are we ready on Wilford? ” questioned Sage. It was Nov. 30, 2018, and through a gray-headed opening, Wilford entered the Travis County courtroom, a sweater peeking out from under his incarcerate costume. His new lawyer, a 42 -year-old with a scruffy beard reputation Andy Casey, patted him on the back. After replying gently to a few questions from the adjudicate, Wilford was taken to jail one last-place era, for processing. With that, he was free.

After almost a year of waiting, it was an anticlimactic ending. Not even his wife was there to celebrate. She’d caught the influenza and was persist at home. To Wilford, the lack of fanfare was perfectly emblematic of how simple his dispute could have been. Casey had announced Christine Wilford as soon as he was appointed to the subject. It had made a few months, but he’d examined the evidence, witness directory and video, then negotiated a deal with the prosecutor: If Marvin Wilford pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor aggression for being involved in the struggle, the felony blames would be lowered. The peak sentence was a year, which Wilford had already sufficed. “The one thing you do ensure him carrying in the video is a cane, ” Casey told me.

A month last-minute, I went to visit Wilford at home in East Austin. For Christmas, Christine Wilford had bought him a pealing to wear next to his wedding party, a epitomize of all they’d been through together. Marvin Wilford had asked for a small business credit to start an online hat shop; his mother had adoration hats, and he planned to listed the bet after her: Marie Antoinette and Lads Hat Shop. He could not speak about Espersen without getting fomented. “How old does a black subject have to be, ” he said, “before y’all stop trying to destroy his life? ”

When I met with Sage soon afterward and asked about Espersen’s caseload, she noted that the numbers can be misleading. Sitting in her place, she pulled up a spreadsheet from her own courtroom. “As of Jan. 2, I have the most cases[ of any justice ], ” she certified — specific, 1,200. “That’s not for the whole year. Just right now.” But one defendant on her roll, for instance, was facing a whopping 20 commissions. Administering 20 subjects for one person, Sage accentuated, is very different from handling the cases of 20 people.

It’s true that caseload figures come with caveats. Casey, for example, is overloaded, hitherto he still managed to give Wilford the necessary attention.( It should be said that Casey’s caseload is not nearly as high as Espersen’s .) But it’s too true-blue that Sage doesn’t deal with 1,200 disputes by herself; she has a team of prosecutors “whos had” their own staff, including investigators and assistants — resources that most defense attorneys do not have. In addition, it’s rare for a single person to face 20 freights; on average, one accused in Travis County has 1.6 pending cases.

I pointed out to Sage that the caseload for a lawyer like Espersen manifests this average: In 2015, for example, his patrons in Travis County numbered 384 and his contingencies 424 — not a huge disparity. Could she actually stimulate the subject, I questioned, that a solicitor with virtually 400 brand-new purchasers a year could perform all of them well, or even adequately? Sage spun back and forth in her chair. “That’s a lot of cases, ” she said. “Lawyers have a personal responsibility. They know what they can manage. Do we really need to tell a solicitor,’ Don’t do that’? ”

That question would swirl around Austin for most of the spring. In a series of heated exchanges, criminal justice reform advocacy radicals, supported by Democratic county commanders, argued publicly that the managed appointed advise sit had not solved either undue caseloads or judicial intervention — and that the only solution was to expand the county’s public defender’s office after all. But resistance from defense lawyers and adjudicators was fierce, and it took until late May for Travis County to submit a proposal to the TIDC.

The proposal expects the commonwealth for about $24 million over five years and devotes the public defender’s office, if expanded, to strict caseload restrictions based on TIDC recommendations.( It likewise asks for more resources for CAPDS .) The TIDC, which received a funding boost from this year’s Legislature of about $14 million a year, must now decide whether to fund the requested state grant; a decision is expected following the completion of August.

Of course, for longtime observers of Texas’ criminal justice system, it’s precisely this piecemeal approaching — a few extra public defenders now, some supplemented fund there — that dooms poverty-stricken defendants to inadequate image. “The only practice to do this correctly is to have a statewide system with standards that’s properly funded, ” said Jeff Blackburn, an Amarillo-based lawyer who founded the Innocence Project of Texas. Class-action litigations are forcing this issue abroad: In New York, for example, after a historic settlement with the New York Civil Immunity Union, the state will spend $250 million a year on indigent works, a burden once shouldered almost entirely by its counties.

It’s likely that no such class-action clothing will take place in Texas anytime soon — the idea of a statewide public defender plan does not have expansive constituency in a lieu this large and diverse — so until then, modify at the country rank will require action by the Legislature. And as a practical purposes, that won’t happen without approval from evaluates, as former mood Sen. Rodney Ellis found out 20 years ago. “Judges who will remain nameless still try and tell me that the judge picking the lawyer is better, ” said Ellis, who is now a commissioner for Harris County, “because they pick people who are capable. How do you say that with a straight face? ”

Even the TIDC is an example of this complicated dynamic. Though by regulation it has the power to set maximum caseloads for advocates across the state, it has never done so. Exclusively the agency’s board can approve such a move, and the board is led by Sharon Keller, the presiding reviewer of the Texas Court of Criminal Entreaty. “We truly do is of the view that beings in the regional province know best, ” she explained to me. When I mentioned that caseload data indicates some solicitors doing what the TIDC’s own study says is the work of at least five solicitors, she replied, “I don’t even know if that’s wrong. The recommendations are a point of reference, and they’re not absolute.”

In the meantime, it may be that litigations at the individual level, like Willey’s, are the surest way to force incremental change. In April, the Houston lawyer learnt his efforts adjudicate calmly when his clothing against Ewing ended with a colonization and both parties concurred “not to generate or ask others to violate the Texas Fair Defense Act.” It wasn’t exactly a daring finish — “Nothing in this settlement should be considered as an admission by Judge Ewing of any wrongdoing, ” read the folders — but Willey realized it as a very limited victory.

“There’s a federal decision now, prescribing that he must agree to follow the law, ” he said.

Meanwhile, Harris County had encountered its own modifications: After a broom of Democratic reviewers came into office in November, the public defender’s office budget nearly double-faced, to $21 million a year. Its juvenile schism — whose lawyers had been receiving an average of 141 lawsuits per year, versus the 300 -plus bags per year given to some private attorneys — had started receiving enough contingencies to hire three more lawyers. The district was also exploring finagled blamed counselor-at-law for its law appointments, including — in a progressive move — a proposal that lawyers adhere to TIDC caseload recommendations.( When the book publication of Texas Monthly with this story went to press, Harris County’s transgression guess had not been able to agreed to such a proposal .) “Travis County did it backward, ” interpreted honcho public guard Bunin, who was feeling hopeful about these changes. “You need a public follower and then a managed named counsel.”

When I last encounter Willey, in June, his fundraising for Restoring Justice was going so well that he’d hired an executive director; he’d also self-assured a partnership with the Houston Texans. But the change in Harris County reviewers had also spelled modification for him. Unexpectedly, he was getting court appointments in Houston and being asked to host fundraisers for friends who were now in the judiciary. That month, he’d been given work in the misdemeanor courts of magistrates Genesis Draper and Franklin Bynum, both former public defenders.

Willey was glad for the appointments, of course, but he was also developing a nagging feel of awkwardnes. He been demonstrated by a sense he’d received from a ally after the story of his settlement with Ewing.

“I hope you didn’t settle because you are going to become like them and forget about justice for all and the underserved community, ” texted the advocate. “I hope you don’t become a good old boy.”

For a hour, Willey looked at his telephone. He would save the word, he said. So that he wouldn’t forget.

A advocate greets: Bill Ray clarifies his workload in Tarrant County

Despite efforts to reach a number of the state’s most overloaded advocates, few agreed to speak for this story. One solicitor who did, however, was Bill Ray, who in monetary 2018 was paid for work on more than 200 felonies, 80 misdemeanors and five uppercase slaughter occurrences in and around Tarrant County, dwelling to Fort Worth.

Ray, like many lawyers and referees in Texas, insisted that caseload numbers can be misinforming. A few of his five capital murder occurrences ought to have going on for several years, he interpreted, and the effort he gets paid for on these in a dedicated time isn’t always intense.( For instance, he might register one flow for a brand-new DNA test .) Not all of the misdemeanour contingencies are work intensive either — numerous, in fact, are probation revocations, in which he represents people accused of violating the terms of their probation. “I usually have one appearance for those, ” he said. “I have a half-hour visit to the jail. That’s it.”

Still, said Ray, “I probably have more occasions than many other lawyers could handle.” There is no caseload limit in Tarrant County. “I don’t ask for these appointments, ” he continued. “I tell the reviewers I’ll do them. I didn’t ask for the capital murder case I got last night. I’m gonna do it.”

Tarrant County has not yet been public defender’s office whose outcomes might have been a baseline for value the work of a court-appointed attorney. But in 2009, one probation revocation example involving Ray did raise some eyebrows. A gal worded Sandra Wilson alleged that, as her lawyer, Ray had discounted clear indications that she had severe mental illness and had tried to kill herself. Her 15 -year prison sentence could have been lowered, she claimed, if Ray had brought up her mental illness.

A federal referee agreed, writing that she might not have gone to prison at all if Ray had brought up her restrictions. The lawyer’s “conduct precipitated below an objective standard of reasonableness, and was outside even the widest range of reasonable professional succour, ” wrote the adjudicate. Ray declined to comment on this case , noting that the judge’s belief should have been shut.( It is easy to find online .) Tarrant County adjudicators have continued presenting him appointments.

When Ray and I spoke in December 2018, he “ve been told” that he did not have any buyers; the bulk of his workload is indicated in the TIDC database. But he did have line-up gigs. In fact, as we were talking on the telephone, he was on his road to see a witness in a case in which the district attorney had recused himself. The justice had appointed Ray — not to defend but to prosecute.

Want a public guard? Take it up with the adjudicator

In numerous Texas provinces, interest in creating more public defender’s offices is growing. To be effective, nonetheless, these public advocates will need both resources and strict caseload restrictions — as in Harris County, where solicitors recently decided to take on no more than 128 offenses a year, down from the present limit of 150. In Dallas County, by comparison, public advocates can be just as overloaded — often more so — than their court-appointed equivalents.( In fiscal 2018, more than two dozen public advocates in Dallas each took on more than 300 offense specimen .)

Crucially, public defense examples will also require buy-in from reviewers, which has not always been easy to come by. In Harris County, for instance, juvenile public guards received ever fewer appointments over several years, so that in 2017 they each had an average load of 140 teenager occasions, which is below the office’s prescribed limit of 200, while a handful of private lawyers — some of whom happened to be generous writers to judges’ campaign coffers — came more than 300. In interviews, two of the county’s juvenile justices insisted that they knew good-for-nothing of these counts and that their court coordinators were in charge of appointments. But since last transgression, when these judges lost their reelection bids, juvenile public defenders have been reporting an increase in their caseloads.

In the Texas Panhandle, where there’s long been a dearth of qualified advocates, a clinic at Texas Tech University Law School began representing consumers from across the region in 2012 who had been charged with misdemeanors. For the first two years, it did so at no charge to provinces that participated; after that, counties must be given to generally pay simply $100 per lawsuit. The clinic’s law students made four misdemeanor occurrences to trial, winning two outright — both of them DWI specimen — and a third, on fraud blames, on petition. In the fourth case, the client was imprisoned of marijuana hold but was sentenced to time he’d once dished — a few days — and blamed a small fine. He’d been facing a sentence of six months.

The clinic seemed like a success, but it stopped receiving appointments from Knox County in 2013 after students won one of the DWI tests. The clinic likewise no longer gets appointments in Garza County, where the stealing occurrence was won on appeal.

The judge who was presided over by misdemeanors in Garza County, Lee Norman, said he stopped use health clinics because of “scheduling issues.”( Patrick Metze, a ordinance professor at Texas Tech, said that the clinic is staffed year-round .) Stan Wojcik, the adjudicator who was presided over by misdemeanor cases in Knox County, said the decision to stop using Texas Tech was procreated before he was elected, but he’s held it in part due to distance: The clinic, in Lubbock, is more than 100 kilometers away. “We do like to use our neighbourhood attorneys, ” he said. “It is easier on clients to have someone local at their jettison. It’s better for them, actually.”

Both adjudicates was pointed out that anyone who needs a lawyer in their districts gets one. Still, Wojcik acknowledged that more lawyers are needed in the Panhandle. “We do have a limited number of lawyers to pick from, ” he said. “Someday, we might need to rethink our operation of Texas Tech.”

The executive director of the clinic, Donnie Yandell, hopes that this will be the case. “Commissioners are always concerned about how money is being spent, and the taxpayer is always concerned about how coin is being spent. We’re charging 100 bucks, and we can’t get appointments. As a taxpayer, I’d be livid.”

Neena Satija is a former reporter for The Texas Tribune and currently a reporter for The Washington Post. This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Howard G. Buffett Fund for Women Journalists.

Disclosure: The University of Texas, the University of Houston and Texas Tech University ought to have financial supporters of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit , nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by subscriptions from representatives, foundations and corporate patronizes. Financial allies dally no character in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

Read relevant Tribune coverage

Exonerated man on Texas request for faster death penalty entreaties: “I would have been executed”

Texas prison system stallings release of public information on hangings

![]()

Read more: tracking.feedpress.it