Antitrust regulators are utilizing the mistaken instruments to interrupt up Big Tech

What we really need is disclosure of information about the growth and health of the afford place of Big Tech’s marketplaces.

It’s a nerve-wracking time to be a Big Tech company. Yesterday, a US subcommittee on antitrust grilled representatives from Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Apple in Congress, and presidential candidates have gone so far as to suggest that these behemoths should be broken up. In the European Union, regulation is already happening: in March, the EU levied its third multibillion-dollar fine against Googlefor anti-competitive behavior.

In his 2018 letter to shareholders, produced this past April, Jeff Bezos was already prepping for conversations with regulators. He doesn’t ponder Amazon is a monopoly. Instead, the company’s founder argues it is “just a small player in world-wide retail.”

In Bezos’s defense, for many of the products Amazon sells, there are countless alternative sources, showing batch of event. Despite Amazon’s leadership in online retail, Walmart is more than doubled Amazon’s sizeas a general retailer, with Costco not far behind Amazon. Specialty retailers like Walgreens and CVS in the pharmacy macrocosm and Kroger and Albertson’s in groceries also dwarf Amazon’s presence in their categories.

But Amazon does not just compete with Walmart, CVS, Kroger, and other retailers–it also rivals with the merchants who sell products through its platform.

This competition isn’t simply the self-evident species, such as the Amazon Basics-branded batteries that by 2016 represented one third of all online artillery marketings, as well as same Amazon produces in audio, home electronics, child licks, bed sheets, and kitchenware. Amazon too contests with its shopkeepers for visibility on its programme, and charges them additional rewards for favored placement. And because Amazon is now heading with featured makes rather than those its customers think are the best, its brokers are incentivized to advertise on the pulpit. Amazon’s fast-growing advertising business is thus a kind of tax on its merchants.

Likewise, Google does not just compete with other search engines like Bing and DuckDuckGo, but with everyone who makes material on the world wide web. Apple’s iPhone and Google’s Android don’t exactly compete with each other as smartphone scaffolds, but too with the app dealers who are dependent upon smartphones to sell their products.

This kind of competition is taken for granted by antitrust regulators, who are generally more concerned with the end cost for customers. And as anyone who has patronized online are aware of the fact, Amazon is nearly always the cheaper option.( In knowledge, examines have suggested that between seven and nine out of 10 Americans will check Amazon to compare the price of a acquire .) As long as the monopoly doesn’t lead to us forking out more coin, then antitrust regulators traditionally leave it alone.

However, this view of antitrust buds out some unique characteristics of digital stages and marketplaces. These whales don’t just compete on the basis of product quality and price–they control the market through the algorithms and blueprint facets that decide which commodities users will see and be able to choose from. And these selections are not always in consumers’ best interests.

A fresh coming to antitrust

All of the internet giants–Amazon, Google, Facebook, and insofar as app supermarkets are considered, Apple–provide the misconception of free markets, in which billions of consumers choose among millions of suppliers’ offerings, which compete on the basis of price, caliber, and availability.

But if you recognise that what buyers actually choose from is not the universe of all possible concoctions, but those that are offered up to them either on the homepage or the search screen, the “shelf space” provided by these platforms is in fact far more limited than the tiniest of regional markets–and what is placed on that shelf is uniquely under the control of the platform proprietor. And with mobile playing a larger and larger role, that digital rack opening is visibly shrinking rather than growing.

In short-lived, the designers of marketplace-platform algorithms and screen layouts can arbitrarily apportion appreciate to whom they choose. The mart is designed and controlled by its owners, and that designing determines “who gets what and why”( to use the prodigious phrase from Alvin E. Roth, who received a Nobel prize in economics for his foundational work in the field of busines designing .)

When it comes to antitrust, the question of market power must be answered by analyzing the effect of these mart layouts on both buyers and sellers, and how they change over time. How much of the value goes to the platform, how much to buyers, and how much to suppliers?

The programmes have the power to take advantage of either surface of their marketplace. Any misuse of sell power is likely to show up first on the render side. A dominant stage can constrict its suppliers while continuing to pass along part of the benefit to consumers–but hindering more and more of it for themselves.

Over time, though, buyers feel the bite. Dominance over dealers eventually translates into power over purchasers as well. As the scaffold owner spares its own presents over those of its suppliers, select is reduced, though it is only in the endgame that shopper pricing–the normal measure of a monopoly–begins to be affected.

The control that the pulpits have over placement and visibility situates them in a peculiar position to collect what economists call fees: that is, appraise obtained through the ownership of a limited resource. These payments may come in the form of additional advantage given to the marketplace’s own private-label products, but too through the costs that are paid by brokers who sell through that stage. These costs can take many forms, including the necessity for brokers to invest more on advertising in order to gain visibility; Amazon concoctions don’t have to pay such a levy.

The term “rents” dates back to the exceedingly earliest days of modern financials, when agricultural land was still the primary source of wealth. That shore was made productively by tenant farmers, who developed ethic through their strive. But the bulk of the benefit was taken by the property gentry, who lived lives of ease on the unearned income that accrued to them simply through the ownership of their gigantic manors. In today’s parlance, Amazon’s merchants are becoming sharecroppers. The cotton subject has been replaced by a hunting field.

Not all tariffs are bad. Economist Joseph Schumpeter pointed out that technological innovation often can lead to temporary leases, as innovators initially have a corner on a brand-new produce or service. But he too pointed out that these so-called Schumpeterian leases can, over experience, become traditional monopolistic rents.

This is what antitrust regulators should be looking at when evaluating internet platform monopolies. Is under the control over the algorithms and designs that allocate attention become the latest tool in the landlord’s toolbox?

Big Tech is increasingly becoming the internet’s landlord–and rents are rising as a result.

In her journal, The Value of Everything, economist Mariana Mazzucato starts the event that if we are really to understand the sources of inequality in their own economies, economists must turn their scrutiny back to tariffs. One of the central questions of classical fiscals was what tasks are actually starting importance for society, and which are merely value extracting–in effect blame a kind of tax on significance that has actually been created elsewhere.

In today’s neoclassical fiscals, payments are considered to be a temporary peculiarity, the result of market flaws that will disappear given sufficient competition. But whether we are asking fundamental questions about value creation, or merely meagre rival, hire extraction pays us a new lens through which to consider antitrust policy.

How internet platforms addition selection

Before digital marts diminished our alternatives as consumers, they first expanded our options.

Amazon’s virtually unlimited virtual rack room radically expanded opportunity for both suppliers and shoppers. After all, Amazon carries 120 million peculiar products in the US alone, compared to about 120,000 in a Walmart superstore or 35 million on walmart.com. What’s more, Amazon operates a marketplace with over 2.5 million third-party vendors, whose products, collectively, provide 58% of all Amazon retail revenue, with exclusively 42% coming from Amazon’s first-party retail operation.

In the first-party retail operation, Amazon buys products from its suppliers and then resells them to purchasers. In the third-party operation, Amazon accumulates fees for marketplace services to sellers–including display on amazon.com, warehousing, sending, and sometimes even financing–but never legally makes self-possession of the companies’ merchandise. This is what allows it to have so many more produces to sell than its competitors: because Amazon never takes property of inventorying but instead charges suppliers for the services it specifies, the risk of offering a slow-moving product is transferred from Amazon to its suppliers.

All of this appears to add up to the closest approximation ever seen in retail to what economists announce “perfect competition.” This expression refers to market conditions in which a large number of vendors with offers to provide analogous concoctions at a range of rates are met by a large number of buyers looking for those products. Those customers are forearmed not only with the ability to compare the price at which commodities are offered, but too to compare the quality of those products via consumer ratings and refreshes. In fiat to win the business of consumers, suppliers does not simply offer very best concoctions at very best tolls, but must compete for customers to express their happiness with the products they have bought.

So far, at least according to the statistics Bezos shared in his annual letter, the success of the Amazon marketplace is a triumph for both suppliers and buyers, and antitrust regulators should be considered abroad. As he employed it, “Third-party marketers are kicking our first-party butt.”

He may well be right, but there are warning signs from other internet marts like Google search that suggest the situation may not be as rosy as it looms. As it is about to change, regulators need to consider some additional factors in order to understand the market power of internet platforms.

How internet platforms take away choice

If Amazon has become “the everything store” for physical goods, Google is the everything store for information.

Even more than Amazon, Google appears to meet the conditions for perfect competition. It parallels up purchasers with a near-infinite source of supply. Ask any question, and you’ll be provided with asks from hundreds or even thousands of rivalling material suppliers.

To do this, Google searches hundreds of billions of web pages are developed by hundreds of millions of information suppliers. Traditional expenditure joining is absent, since much of the content is offered for free, but Google operations hundreds of other signals to determine what explanations its clients are likely to find “best.” They measure such things as the honour of the places joining to any other site( sheet grade ); the words those websites use to meet those connections( secure text ); the content of the document itself( via an AI engine referred to as “the Google Brain” ); how likely beings are to click on a yielded to be translated into the roll, based on millions of iterations, all recorded and assessed; and even whether beings clicked on a join and appear to have gone away fulfilled( “a long click”) or came home and sounded on another( “a short click” ).

The same falls for advertise on Google. Its “pay per click” ad auction model was a breakthrough in the direction of perfect competition: advertisers compensate only when clients click on their ads. Both Google and advertisers are thus incentivized to feature ads that users actually want to see.

Only about 6% of Google search results sheets contain any promote at all. Both content producers and purchasers have the benefit of Google’s immense effort to index and examine all web pages , not just those people who have commercially valuable. Google is like a supermarket where all of the goods are free to buyers, but some merchants offer, in the form of advertising, to have their goods sat figurehead and center.

The company is well aware of the risk that ad will guide Google to favor the needs of advertisers over those of searchers. In fact, “Advertising and desegregated motives” is the title of the appendix to Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin’s original 1998 research paper on Google’s search algorithms, written while they were still graduate students at Stanford.

By placement on the screen and algorithmic priority, programmes have the power to shape the pages customers click on and the products they decide to buy.

“The goals of the advertising business model do not always correspond to providing quality search to users, ” they thoughtfully detected. Google impelled enormous efforts to overcome those desegregated purposes by clearly separating their publicizing results from their organic develops, but the company has blurred those frontiers over hour, perhaps without even recognizing the extent to which they have done so.

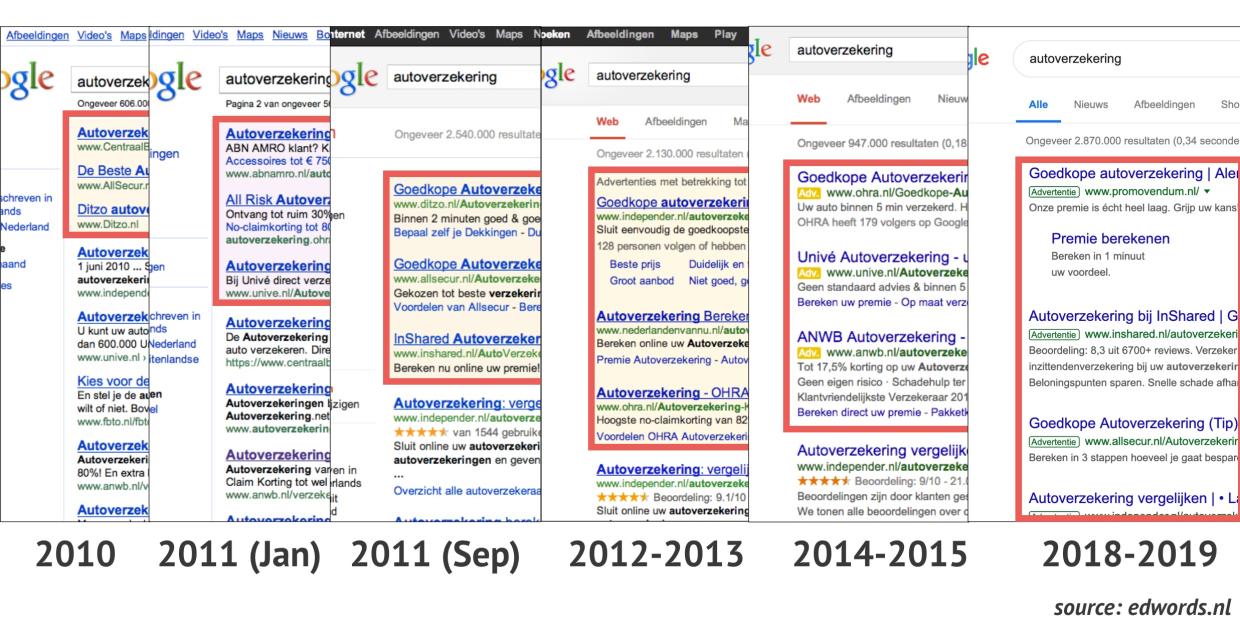

It is undeniable that the Google search results sheets of today looks a lot like they did when the company went world in 2004. The list of 10 “organic” reactions with three paid leanings on the top and a sidebar of pushing answers on the right that once stamped Google are long gone.

Dutch search engine consultant Eduard Blacquiere substantiated the changes in size and placement of adwords( relation in Dutch ), the pay-per-click advertisements that run alongside searches, between 2010 and 2014. Here’s a sheet he captured in June 2010, the result for a sought for the word “autoverzekering”( “auto insurance” in Dutch ).

Figure 1. Screengrab: Eduard Blacquiere.

Figure 1. Screengrab: Eduard Blacquiere.

Note that the adwords at the top of the sheet have a background tint, and those at the side have a narrower column width, defining both off clearly from the organic reactions. Take a immediate glance at this page, and your heart can quickly jump to the organic ensues while rejecting the ads if that’s what you prefer.

Here is Blacquiere’s dramatization of the change in size of that top block of adwords. As you can see, the ad block has both dramatically changed in size and lost its background color between 2010 and 2019, spawning it much harder to distinguish ads from organic results.

Figure 2. Screengrab: Eduard Blacquiere.

Figure 2. Screengrab: Eduard Blacquiere.

Today, paid makes can push organic reactions almost off the screen, so that the searcher has to scroll down to see them at all. On mobile pages with ads, this is almost always the case. Blacquiere likewise documented the result of various studies done over a five-year period, which witnessed the probability of a click on the first organic hunting develop fell off over 40% in 2010 to less than 20% in 2014. This shows that through changes in homepage design alone, Google was able to shift significant attention from organic search results to ads.

Not merely is paid advertising supersede organic search results, but for more and more queries, Google itself has now compiled enough information to provide what it considers to be the best answer instantly to the consumer, eradicating the need to send us to a third-party website at all.

That’s the box that often performs above the search results when you ask a question, such as What are the lyrics to “Don’t Stop Believing, ” or What date did WWII end?; the box to the right that dads up with restaurant reviews and opening hours; or a series of visual cards midway down the screen that picture you the actors who appeared in a movie or all types of tarts common to a geographic region.

Through changes in homepage design alone, Google was able to shift significant attention from organic search results to ads.

Where does this information come from? In 2010, with the acquisition of Metaweb, Google committed to a project it announced “the knowledge graph, ” a collecting of actualities about well-known entities such as residences, people, and affairs. This lore graph caters immediate refutes for many of the most common queries.

The knowledge graph was initially culled from the web by ingesting knowledge from informants such as Wikipedia, Wikidata, and the CIA Factbook, but since then, it has become far more encyclopedic and has ingested information from all over the web. In 2016, Google CEO Sundar Pichai claimed that the Google knowledge graph contained more than 70 billion facts.

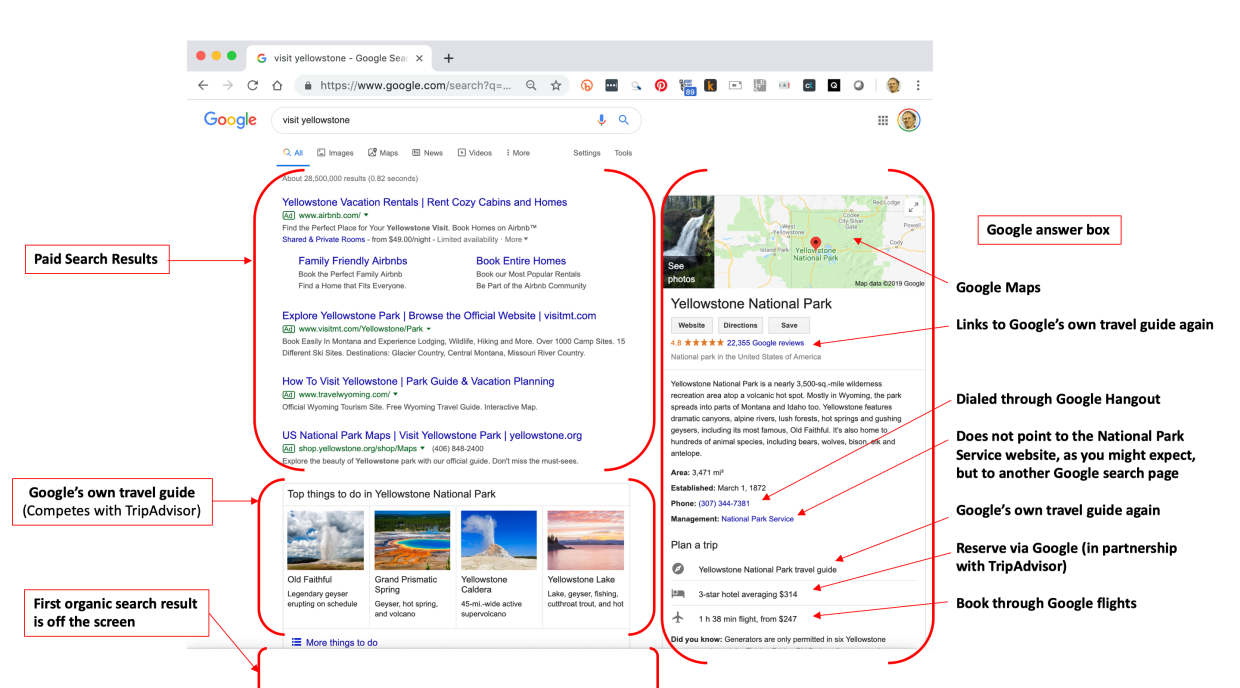

As shown in the figure below, for a popular search that has commercial-grade possible, like inspect Yellowstone , is not simply is the search results page dominated by paid search results( ads) and material immediately supplied by Google, but Google’s “answer boxes” are themselves filled with links to other Google pages rather than to third-party websites.( Note that Google personalizes results and also lopes hundreds of thousands of A/ B assessments a daylight on the effect of minor changes in position, so your own answers for this identical search may have different answers than are shown here .)

Figure 3. Screengrab: Tim O’Reilly.

Figure 3. Screengrab: Tim O’Reilly.

As of March 2017, user clickstream data provided by web analytics conglomerate Jumpshot suggests that up to 40% of all Google inquiries no longer result in a clink through to an external website. Think of all the questions you go to Google for that no longer require a second click: what’s the forecast? What’s the current value of the euro against the dollar? What’s that song that’s playing in the background? What’s the best neighbourhood restaurant? Biographies of prominent parties, descriptions of municipals, vicinities, business, historic event, repeats by famed writers, song lyricals, broth prices, and flight days all now appear as immediate answers from Google.

I am not certainly recommending anti-competitive intent. Google claims, with great justice, that all of these changes to search engine result pages are designed to improve user experience. And indeed, it is often helpful to get an immediate answer to a query rather than having to click through to another web site. Furthermore, much of this data is in fact licensed. But these lots seem like a step backward from the excellent contender represented by Google’s original trust on multi-factor search algorithms to surface the very best information from independent web sites.

The net result on Google’s financial action is striking. In 2004, the year that Google moved public, it had two principal advertising income engines: Adwords( those pay-per-click advertisings that run alongside probes on Google’s own locate) and Adsense( pay-per-click circulars that Google targets on third-party websites on their behalf, either in search results on their site or directly alongside their content ). In 2004, the two revenue roots were very close to equal. But by 2018, Google’s revenue from advertising on its own qualities had grown to 82% of its total advertising income, with simply 18% coming from the advertising it supports on third-party sites.

These lessons represent the ability of a pulpit to chassis, both by placement on the screen and algorithmic priority, the sheets useds click on and the products they decide to buy–and therefore likewise the financial success for the quantity surface of its marketplace. Google maintains a rigid disconnect between the search and marketing crews, but despite that fact, changes in the layout of Google’s sheets and its algorithms have played an enormous role in shaping the attention of its consumers to favor those who advertise with Google.

When Google decides unilaterally on the immensity and position that its own products take over the screen, the committee is also stops shoppers from organically deciding what material to click on or what socks to buy. That’s what antitrust regulators should be considering: whether the algorithmic and motif ascertain utilized by places like Google or Amazon abbreviates the choices we have as consumers.

Maintaining the apparition of selection

If Google has monopolized our access to information, Amazon’s fast-growing advertising business is now shaping what products customers are actually given to choose from. Have they, more, taken little bit from the poisoned apple of advertising’s mixed intentions?

Amazon’s sellers are becoming sharecroppers. The cotton battlefield has amended by replacing a rummage land.

Like Google, Amazon used to rely heavily on the collective knowledge of its customers to recommend the best commodities from its suppliers. It did this by utilizing datum such as the supplier-provided description of the product, the number and quality of scrutinizes, the number of inbound connects, the sales rank of similar concoctions, and so on, to determine the seek in which search results would appear. These were all factored into Amazon’s default search standing, which leant concoctions that were considered “Most Popular” first.

But as with Google, this eden of internet collective ability may be in danger of coming to an end.

In the sample below, you can see that the default search for “best science fiction books” on Amazon now turns up only “Featured”( i.e ., paid for) produces. Are these research results you’d expect from this search? Where are the Hugo and Nebula award champions? Where are the books and generators with thousands of five-star re-examines?

Contrast these results for those for the same search on Google, shown in the figure below. A knowledgeable science-fiction supporter might quibble with some of these excerpts, but this is indeed a directory of widely acknowledged classics in the fields. In this case, Google presents no marketing, and so the results instead simply wonder the collective intellect of what the web thinks is best.

While this might be taken as a thinking of the superiority of Google’s search algorithms over Amazon’s, the more important point is to note how differently a pulpit discuss decisions when it has no particular business axe to grind.

Amazon has long claimed that the company is fanatically focused on the needs of its purchasers. A investigation like the one indicated above, which praises paid arises, demonstrates how far the quest for advertising dollars takes them from that avowed goal.

Admonition for antitrust regulators

So, how are we therefore best is to determine whether these Big Tech programmes need to be regulated?

In one famous exchange, Bill Gates, the founder and former CEO of Microsoft, told Chamath Palihapitiya, the one-time head of the Facebook platform 😛 TAGEND

“This isn’t a scaffold. A platform is when the economic value of everybody that uses it excess the value of the company that creates it. Then it’s a platform.”

Given this understanding of the role of a platform, regulators should be looking to measure whether companionships like Amazon or Google are continuing to provide opportunity for their ecosystem of suppliers, or if they’re increasing their own returns at the expense of that ecosystem.

Rather than just asking whether buyers benefit in the short term from the companies’ acts, regulators should be looking at the long-term health of the markets of suppliers–they are the real root of that consumer help , not the scaffolds alone. Have Amazon, Apple, or Google deserved their gains, or are they coming from monopolistic payments?

How might we know whether a company operating an algorithmically organized marketplace is removing leases rather than simply taking a reasonable slash for the services offered it accommodates? The first sign may not be that it is raising costs for shoppers, but that it is taking a larger percentage from its suppliers, or competing unfairly with them.

Before antitrust experts look to rectifies like breaking up these companies, a good first step would be to require disclosure of information about the growth and health of the furnish slope of their marketplaces. The statistics about the growth of its third-party marketplace that Bezos trumpeted in his stockholder letter tell only half the narrative. The questions to ask are who advantages, by how much, and how that allocation of rewards is changing over time.

Regulators such as the SEC should require regular monetary reporting on the allocation of value between the programme and its marketplace. I have done restraint analysis for Google and Amazon based on information provided in their annual public filings, but much of the information needed for a stringent analysis is just not available.

Google equips an annual economic impact report analyzing value provided to its advertisers, but there is no comparable report for the quality created for its content suppliers. Nor is there any visibility into the changing fates of app suppliers into the Play Store, Google’s Android app marketplace, or into the riches of the information contained providers on YouTube.

Questions of who gets what and why must be asked of Amazon’s marketplace and its other operating gangs, including its reigning cloud-computing department, or Apple’s App Store. The capacity of Facebook’s algorithms for the purpose of determining what content appears in its readers’ newsfeeds has been considerably investigated with respect to political bias and manipulation by hostile actors, but there’s been little thorough fiscal analysis of economic bias in the algorithms of any of these companies.

Data is the currency of these companies. It is likely to be the currency of those looking to regulate them. You cannot regulate what you don’t understand. The algorithms that these companies use may be defended as trade secret, but their sequels should be open to inspection.

Continue reading Antitrust regulators are using the erroneous tools to break up Big Tech .

Read more: feedproxy.google.com